Marcel Duchamp Switched to Chess - But Wait: Before that, this Eccentric Baroness Sent Him a Toilet For Which He Later Became Quite Famous. . .

/Marcel Duchamp's impact in the genesis of modern conceptual art was revolutionary. For one, he produced the famous Nude Descending a Staircase:

Then he gave up painting in order to play chess full time.

The idea of Duchamp playing chess in lieu of making art was fascinating and puzzling. While visiting visiting D. Adler and Delores Furtado at their home in Brooklyn and sitting in their kitchen discussing this, Delores, a sculptor, pointed out The Fountain, Duchamp's famous porcelain urinal, and his most famous "Ready Made" (those objects of utility, recognizable and common place, which had challenged the convention of artistic definition of the time), perhaps hadn't been his idea after all.

I redirected my searches away from chess to the source of Duchamp's sculpture: The Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Lorinhoven. She'd been a wildly creative collagist and assembly artist of found objects for several years prior to Duchamp announcing the Ready Made line.

The toilet had been sent to him by this eccentric woman already branded with the famous R. Mutt. In 1917, Duchamp wrote his sister how "one of my female friends under a masculine pseudonym, Richard Mutt, sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture." Duchamp submitted the urinal to the 1917 exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in New York, under the artist's name Richard Mutt. They declined to exhibit the piece even though the show's explicit intention had been to present each of the works submitted. The judgement implied the object could not be considered art by the panel's definition.

R. Mutt, it was later conjectured, had been the Baroness' play on the German armut, meaning poverty, and in that context, further implied intellectual poverty. Years later, after the baroness and the original photographer had passed, Duchamp insisted the sculpture was his creation solely.

The Baroness did issue a rebuttal of abandonment in the form of a 1923 painting entitled: Forgotten Like This Parapluie Am I By you - Faithless Bernice. In it, she depicts the toilet with Duchamp's pipe sitting on the rim.

Much has been made of Duchamp playing chess. Records of his matches are available, articles have been written on a chess problem he bequeathed as well as his particular interest in the endgame. Several art critics inferred that his chess activities and further, the spirit and logic of a chess match, was synonymous with Duchamp's self-definition as artist. In that way, his reluctance to outwardly involve himself in the art world was consistent. Duchamp chose a more concrete world of ideas over the institution of imagery.

"If Bobby Fischer came to me for advice, I certainly would not discourage him—as if anyone could—but I would try to make it positively clear that he will never have any money from chess, live a monk-like existence and know more rejection than any artist ever has, struggling to be known and accepted."

Duchamp appeared gaunt and drawn to me in his later photographs, like the face of an inveterate gambler, a man in debt. Dostoyevsky's later likenesses were similar. Could Duchamp have been at once a man of ideas and a man in conflict? Imagined in the extreme, could Duchamp have been pressed to death, slowly, internally, as they had pressed the witches of Salem, the judges, his own internal interlocutor(s)? That Duchamp's turning to chess and away from art did not represent an intellectual or even aesthetic response, but the act of someone with something to hide? Who knows. A conjecture solely based on glances at photographic likenesses is flippant and presented here solely as a reminder of the broad spectrum of unknown human possibility. A pensive man can certainly be seen, one side of the mouth, curling with faint irony. Duchamp was someone of such obvious enormous influence and thoughtfulness. He must have "known what he was doing."

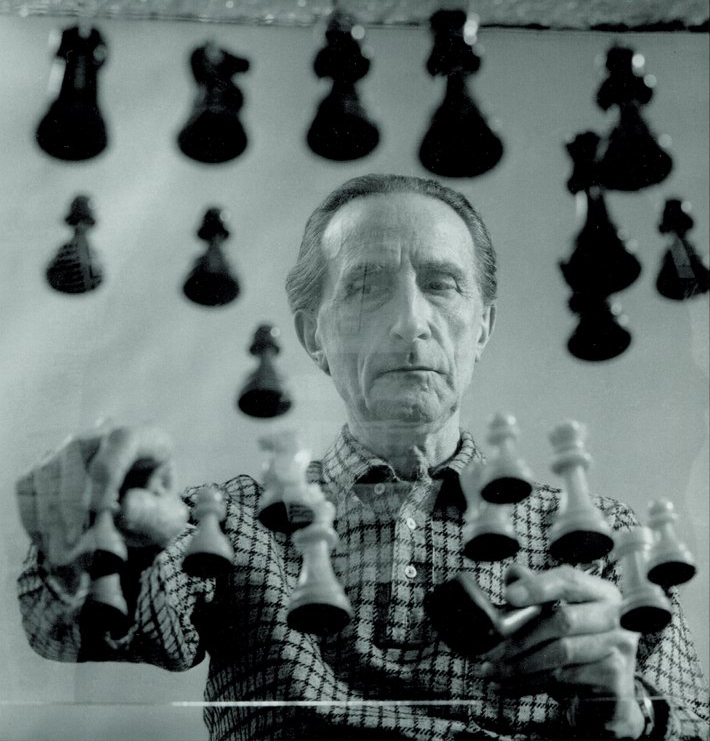

Arnold Rosenberg, Marcel Duchamp playing chess on a sheet of Glass, 1958

With regard to his relationship to the crazy baroness, whom he earlier spoke of as a genius then later, distanced himself: Truth can and does remain hidden, in art, as in politics, and certainly, individual truth. We live in an age of fallen heroes, and in that, God has died a couple of times. We can no longer place our absolute trust in individuals of stature. It seems entirely possible this little known eccentric baroness, this unsung hero, came up with at least a few of the seminal ideas credited to him.

The baroness

Arising from the scouring material and clarification of this baroness's role in the history of twentieth century art, I discovered a wonderful book: Stranger Than We Can Imagine: Making Sense of the Twentieth Century, written by John Higgs and published by Weidenfeld and Nicolsen. Broadly eclectic in its scope, Higgs explores the subjectivity of viewpoint in both the arts and sciences of the 20th century, the relativistic outlook leading toward postmodernism: absolute truth does not exist.